This post is the first in a series on the yoga industry. The topics here are inspired by questions from practitioners who have learned yoga as a strictly person-to-person oral transmission in a grassroots setting (the shala where I teach) and only later encounter the modern asana climate beyond our shala. The ideas are further shaped by 3 years in the non-profit world, 6 years of waiting tables, and by 7 years of graduate study in historical and economic sociology at UCLA. My graduate mentors were the late Peter Kollock and by other professors who would not prefer to be cited on a yoga blog. More questions for this series are welcome.

There is a script for the self who teaches yoga. Your industry bio requires the following elements.

(1) A description of how you found yoga, or how yoga found you.

(2) The symbols printed on your receipt (RYT- 200, 500, etc.)

(3) A list of people whose workshops you have taken (“studied with.”)

(4) Some unique adjectives for the flavor of your class.

(5) A quirky-wise-individualistic sentence on what yoga means to you.

Capitalism is smart. This is an example. In the space of a text box in the MINDBODY Online ™ software, you (the yoga teacher) and yoga have been cast as commodities. The text box bio denotes the class for sale, and also represents a success story in the consumption of the larger-sized yoga units (workshops and trainings) that one can also buy from the studio. The teacher’s work has been characterized as a kind of hobby (exactly the kind of work that should be part time and contingent), and his consumption of TTs and workshop has been legitimated as the mode of expertise-accumulation for teachers.

One of the commodities generated by this definition of the yoga teacher is relatively cheap (the teacher’s labor). And one is not (the good/service called yoga, available in 90-minute, weekend-long, and 200-hour sized packages). As long as teachers agree to these definitions of the situation, the loop of yoga production and consumption will spin without resistance.

So, what’s the problem? No problem.

First, teaching asana classes for one’s community is a good hobby. A person who does it for 3 hours per week does well to take weekend workshops to sharpen up her alignment skills and place the practice of asana in historical context. If she is using asana teaching an outlet for service, then there is no reason to approach the work with a professional mindset or to put a ton of energy into examining the relationship between capital-Y-Yoga and group classes on posture. The hobbyist resume is a good model in this case.

Second, the yoga bio is just commodification doing what commodification does. It’s natural. Turning experience into things that can then be traded for money is capitalism’s job, and if you go with the flow consciously sometimes you can direct this process to the greater good. Commodification isn’t bad. It is not art; it does not (cannot) treat learning as an end in itself; it does not support the notion of pricelessness. Still, commodification just happens. It can be a value neutral process. Studios that commodify yoga and teachers’ labor are actually not evil. They are effectively speaking the common tongue.

BUT. Well, two big things.

If you are still reading, probably you have far different standards than a profit-driven studio for (1) what constitutes a yoga teacher, and for (2) what is yoga. So it’s appropriate to use different language entirely to describe the work and the subject matter.

It may even be possible to use language as a tool to resist the alienation process that commodification promotes – a process in which workers become detached from the deep value of their work, or the work itself gets detached from the essential creative energy it once contained. (On which: look up “sensuous human activity.” Work that expresses the life force is in essence erotic. Marx said that, not me.)

This post magnifies the yoga bio as a tiny common moment of yoga commodification, so that devotional practitioners might see different options. They might change the symbolic terms of engagement. Why bother? Because: does the yoga studio logic make sense for devotional, lineage-based practice? Is yoga about uncritically reproducing mass culture? Is yoga socially transformative? Is yoga punk rock? Is teaching an art? Are relationships a service rendered for a fee, or something outside of the market? Let’s talk options.

Item 1 (how you found yoga) above puts yoga in the category of “after work hobby.” Contingent, part-time, contractual workers have hobbies. Not professionals. People who have a day job find their hobbies by happy accident. QED.

Item 2 (reference to a TT for legitimacy) eclipses merit-based selection of teachers, and merit-based blessings to teach. Receiving a call, and receiving a blessing, based on merit, is essential to parampara. An RYT designation, by contrast, indicates a service that was paid for, and that anyone else can purchase too. That’s capitalism. Money is its own standard.

Item 3 (workshop list) defines student-teacher relationship as short term and non-exclusive.

With many teachers come many lines of action. And no necessary follow-up from either party. There is not a shared project between teacher and student. By contrast, the long-term, semi-exclusive relationships of devotional practitioners are characterized by mutual accountability.

Item 4 (description of what makes your class special) implies that yoga needs to be branded. Make it creative. Put your spin on it.

Item 5, (what yoga means to you) like item 1, is unprofessional. Does the sociologist conclude her bio with a statement on what society means to her? Or the psychologist tell you what the psyche means to him? From a professional standpoint, devotional practitioners understand that there is a difference between Yoga, and the particular personal questions we trying to resolve through practice at this time. “What yoga means to me” is transitory, because we are life-long students. That changing interpretation may condition how we pass on the methods we have been given, but it doesn’t define the student experience. Students are invited to engage with a Yoga that is bigger than the teacher.

More regarding item 3. Using workshops (rather than enduring relationships) as the mode of continuing education gives studios another thing to sell. The illusion of relationship is created (and commodified) with photos of momentary interactions. This process effectively alienates the workshop teacher from his labor, which in a devotional setting would rightly be found in the form of grounded, long-term, mutually accountable relationships. But what about workshop teachers who don’t care about such things at all, because they aren’t actually grounded in a lineage?

This is where the yoga bio gets fishy. If traveling experts give a bio in the hobbyist format, all we truly know about how well is how well he might entertain us. We don’t know if the person claiming expertise has an unbroken history of practice, or if he has passed any benchmarks with teachers or institutions that provide merit-based review and long-term accountability (and the possibility of losing one’s license). We don’t know if the traveling expert has an ability to choose good teachers of his own and nurture healthy relationships with them over decades. Most importantly, because traveling experts are from elsewhere, one doesn’t get the chance to evaluate who they really are as everyday people, or learn about them from the family and colleagues who know them best. But going to the trouble to get into the bona fides of this sort does not necessarily serve the commodification of yoga. What serves the commodification of yoga is experts who are charismatic and entertaining.

Ok. So you are not a hobbyist. Your personal daily practice comes first, and you have chains of accountability to both teachers and students. Teaching is something you have been called to do, and blessed to do. You teach because your teacher told you do to so, and because you deeply need an outlet for service. What language and class models do justice to this?

I don’t know, but where I started was by looking at how the hippies did it. Did that that first generation of western yoga teachers who studied in India think critically about capitalism? Maybe they were just genius keeping the yoga close to the ground, no matter the circumstances. Maybe their transmission was clear simple because they experienced the yoga as priceless, or because cultivating a bit of inner freedom from materialism and greed was one of the achievements of their particular zeitgeist. Whatever it was, the shalas the first generation started were no frills. Not a lot of bling in the brick and mortar, but all kinds of continuity in the habit of practice and realness in the relationships between people.

A few of this generation even pioneered the workshop model without commodifying yoga. Take a look at what Nancy Gilgoff and Peter Sanson have been doing without fanfare for 30 years. In the rare cases that they teach away from their own schools (which is where you really go if you want to absorb what it is they are living and transmitting), they travel to communities where they have a long-term relationship with the director. They decline requests from people they don’t know. Instead of looking for new markets (the imperative of capitalism is constant expansion into new consumers and new products), they just keep returning to the places they have been before. Because they take responsibility for following up on the instructions they have given in the past. And they have a long trajectory of fellowship with given individuals and groups. They’re not tossing their seeds haphazardly; they are cultivating ground they understand to be fertile. Karl Marx would be proud: they have created and shared their work without becoming alienated from it. Talking with one of the long-term attendees of this kind of workshop reminds of talking with Burners. They may not have made the greatest sacrifices or taken the craziest pilgrimages in search of the self, but they have been repeatedly, indelibly marked by an experience in a way that is too much a part of them to put in to words. They haven’t taken those workshops to get a piece of said teacher; rather that experience has become a piece of them.

Back to items 1-5 above. A devotional teacher does not have 200 hours of training; she has thousands of hours. You teach because your teacher trained you to do so, and gave you a blessing that entails both rights and duties. You invest a majority of your energy in personal practice and study. You have been practicing daily for a decade and more. You go to great lengths to be with your teacher – not for thematic sessions, but for the sake of hanging out in the same context where he carries on his daily life. You do this for months at a time, with nothing to be gained in the career realm. You’ve made so many weird life choices that you’ve lost the concept of “sacrifice” – practice is just the organizing principle of your life, in a way people of the mainstream find weird, sometimes offensive, and definitely punk rock. This makes you an outlier among yoga teachers, you know. Why not let the devotional flag fly?

How? Sadly, using the word “devoted” in your bio doesn’t help. The word is everywhere in yoga bios and is used to signify an emotion the teacher feels, not actions she caries out daily. Generally, adjectives won’t help. But facts… your facts can talk.

Here is everything I want to know about a teacher.

(1) When did she start practicing?

(2) How long has he had a daily practice without a break?

(3) Who have all her teachers been – not just the famous or convenient ones.

(4) Who is his teacher? That is, who trained and blessed him to teach, and whom do I go to if he screws up?

(5) How exactly does she make herself a student? What are her plans for time with her teachers in the future?

There’s a bio, right there. Just the bona fides.

_____________________________________________________________

P.S. Insideowl sends a short monthly newsletter, insideout.

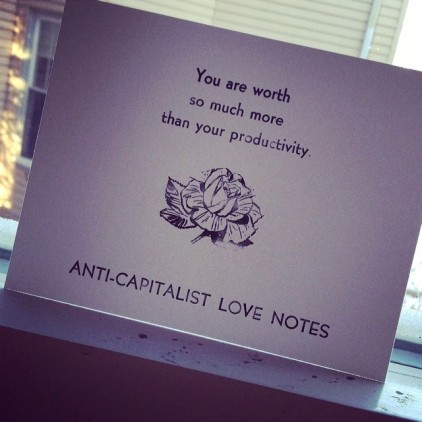

P.P.S.The image above is the creation of emprints, who gives her blessing for its use here.

11 Comments